Appreciation or appropriation?

June 23, 2023

By Coral Madge, Steward, Indigenous Collections

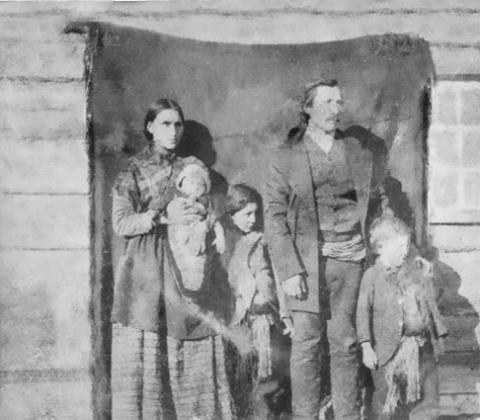

When I was a young boy, I would sit at my mother’s feet and she would braid my hair before bed. I remember reaching behind me and touching the beadwork on the moccasins her grandma had made for her — noticing the smell of smoked moose hide and the texture of beaver fur as my fingertips traced the curves of the petals and leaves. As I grew, I asked my mom to teach me to bead like she did with her grandma and she pulled out our family’s collection of beads, many passed down from my great grandmother Emily Villenuve.

My mom taught me how she had learned to bead. “Keep the tension even so they lay flat. That’s where you show skill and beauty.” As we sewed, she told me stories of growing up and the old fort at the Fort Nelson River. She told me of speaking Slavie and sewing with elder Mimi Needlay and her grandma, and shared stories of being on the land with her dad, Earl.

This moment was a seed in my life that I nurtured and grew over the years. I started beading for my family and friends and soon started to get commissions. I learned how to speak the language my mom grew up speaking. I sat with knowledge keepers who taught me hide tanning, quillwork, and tufting as well as floral motifs and their names. My great Auntie Pauline would guide me and tell me how her mom used to sew. I learned the inheritance of design, my great grandmas hand drawn floral patterns and beads passed down to my hands. I also learned of the artists that came before me, including my fourth great grandmother Marie Madeline Bouvier, the first tufting artist.

Through the community that guided me, I learned many things that made me the artist I am today, like how to be a traditional artist, the cultural responsibilities tied to these traditions or that harvesting materials from the land it must be done in a good way. I learned to replace what you have taken with tobacco and commit to using what you took for a good cause. Indigenous artwork is not just a reflection of an artist’s vision but also generations of relationships to the gifts the earth has given us.

This cultural importance and the stories of artists are a vital part of discussions on cultural appropriation. It is crucial to know that many Indigenous designs are an imprint of all the teachings and cultural experiences the artist has been through. There are deep complexities to this artistic history as well; understanding that for hundreds of years our art was destroyed and replaced with lifeless imitation based on stereotype instead of proper experience. With every stitch and brush stroke, Indigenous artists infuse their work with spirit and use this cultural artistry as an act of peaceful protest for all that is against us as Indigenous people.

The designs and techniques used in Indigenous art and craft are living, and carry the weight of our ancestors. When we homogenize Indigenous designs or rely on stereotype, we lose this inheritance.

A good story of this cultural perspective on artwork is that of Mrs. Matt, an Apache basket maker. Mrs. Matt was hired to teach a basket making class at a local university in America and after three weeks, students were confused and complained that they were still only learning songs. They brought up their concerns, asking to confirm that it was a basket weaving class and not a singing class. Mrs. Matt shared that the songs were a part of the process — before the fibres were collected, they needed to be sung to in order to avoid offending the plants and gain permission before harvesting them. In time, fibres were collected and students again complained of the long process and having to learn songs as they softened these fibres. Mrs. Matt was taken aback and told them “you are missing the point.” She explained that these baskets are not about the end result. What they were creating was more than just that. She told them “a basket is a song made visible.”

Mini Apache burden basket, from the RAM Indigenous Collection

The emphasis in that story is to make things in a good way while understanding and carrying these teachings. Without being from the culture you cannot connect to these hidden things. As a Dene and Métis-Cree artist I do not know what it means to be a Blackfoot artist, or a Scottish artist, or an Apache basket weaver, nor do I have the inheritance to use their designs. I cannot create medicine from things that are not my own. When talking about these things with Dorothy Buckley, Dene artist and elder from Kátt'odeeche First Nation, she encouraged me to keep our artistic teachings in our community. She told me “Esjia anyway Móla ke ats'ọọze nahxį Dene híídlį azhọ ahsíí keogedí?á héníndé sets'ę genidhę, ehtth'ile,” meaning, it’s a bad thing when Dene ways of doing things are done by Europeans who claim it as their own.

I understand why this powerful artistic movement is attractive to those outside our communities. There’s a fascination with how we see the world. There’s also those that look at our designs with greed. People want to create what they see as an end product but do not understand all that goes into it and in doing so, they miss the point of the act of creation. Appropriation of Indigenous art takes away our power to tell the world who we are on our own terms. We are in a time when cultural art theft is rampant with very little legal protection for Canadian Indigenous artists whose designs are stolen and mass produced to create profit for non-Indigenous companies. The United States have the Indian Arts and Crafts Act (1990) as well as the creation of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (IACB), which assists tribes and individuals with legal fees in pursuing action against those that sell Indigenous items who are not Indigenous. Currently there is a push to have a similar process here in Canada.

There are things that non-Indigenous people are invited to join in on to learn and understand who we are as people. To support Indigenous artists and the important cultural work that they do is to listen to who they say they are. Support them by buying their artwork. There are things that we make for everyone. I make moccasins and jewellry for everyone. My great grandma Emily supported herself by selling her work in her community and to government officials that would visit her community. Today there is a huge movement of Indigenous makers creating careers through their work. By buying directly from Indigenous artists you are supporting cultural revival and small businesses. You are putting meals on their table. I remember how excited I was when I would get orders that would pay my bills and secure my rent for that month. By purchasing artwork from Indigenous artists, you are celebrating who they are, their story, and the revival and continuation of their culture.

If you are looking to purchase Indigenous artwork, take the time to understand who you are buying from. It’s in our teachings that what a person makes becomes an imprint of their spirit. Artists that make things in a good way will carry that medicine of good intention. If you are unsure if the work is “Indigenous inspired” or if it is from inspired Indigenous, look into their company or who made the item. A simple Google search can tell you if it is an Indigenous artist behind the design or not. Many Indigenous artists are included on lists, such as the Indigenous Arts Collective of Canada, that are organized to show you a list of mediums and help you connect with artists individually. There are also companies like Eighth Generation and Manitoba Mukluks that give platforms to Indigenous artists to sell their work. There are many lists like this available on different platforms that you can check. Also, I recommend looking at the artist’s profile to see if they identify themselves as Indigenous. It’s important to take the proper time to know what it is you are supporting.

There is beauty in our work; sewing, painting, carving, and the many other forms that creativity can take. You are welcome to join in the experience of our stories made physical. Support the people that speak for themselves and be careful of those that try to speak for us.