Chinese Head Tax: George Yee's Story

By Julia Petrov, Curator, Daily Life and Leisure,

And Matthew Ostapchuk, Acting Curator, Military and Government History

May 10, 2021

The artifact we are highlighting this week has a sad resonance today. With levels of anti-Asian hate and racism rising, we want to show how far Canadian society has come, but also how far we still have to go toward the kind of inclusive culture to which we aspire.

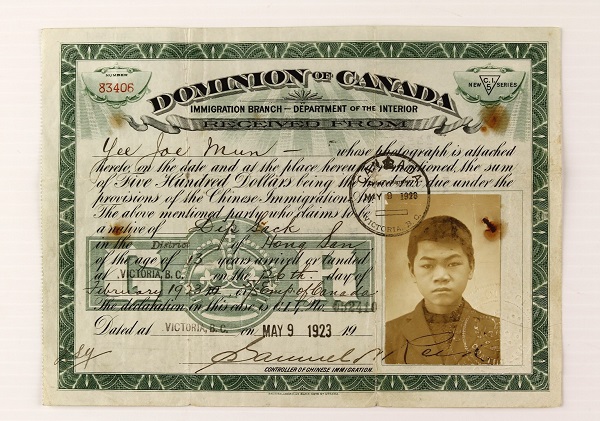

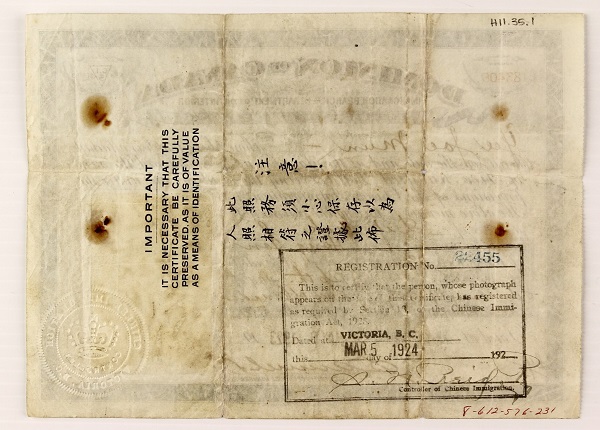

This is an official government document - a so-called Head Tax certificate. Issued on May 9, 1923, in Victoria B.C., it is signed by the 'Controller of Chinese Immigration', Samuel N. Reid. The green and black certificate features a photograph of a Chinese boy, Joe Mun "George" Yee, (1910 – 1978). On the back, instructions printed in printed in English and Chinese exhort: "IMPORTANT / IT IS NECESSARY THAT THIS CERTIFICATE BE CAREFULLY PRESERVED, AS IT IS OF VALUE AS A MEANS OF IDENTIFICATION".

Between 1881 and 1885, 15,000 Chinese labourers came to Canada to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway. They faced harsh and dangerous conditions, long hours, and less pay than other workers. When the railway was completed in 1885, the demand for labour decreased and the government introduced the Head Tax to stop the flow of Chinese immigration to Canada. Head Tax certificates were in use from 1885 to 1923. The Head Tax was only imposed on immigrants from China and was intended as a means to restrict Chinese from entering into North America (both Canada and the US imposed this tax). Originally costing $50, the tax was increased to $100 in 1900 and to $500 in 1903, where it remained. The certificates were really receipts marking the payment of the tax. They were typically issued from Canton province in China (point of origin) but were also issued in Victoria and Vancouver, BC (ports of landing). Head Tax certificates were the earliest example of photo identification issued by governments in North America. At this time, individuals of Chinese descent living in Canada were not eligible for citizenship, and had no legal status, whether immigrant or Canadian-born. Chinese Canadians who served for Canada in the Second World War fought for citizenship and the right to vote for all Chinese Canadians, which was granted in 1947. Until this time, the Head Tax certificate remained a primary identification paper for Chinese Canadians.

The 13-year-old George Yee arrived in Canada just a month before the Head Tax was supplanted by the passing of the Chinese Immigration Act, which effectively banned all immigration of Chinese Nationals to Canada (fewer than 50 Chinese people were allowed to immigrate to Canada between 1924 and when the Act was repealed in 1947). George’s certificate has a second stamp dated 1924, marking the new law and his effective exclusion from Canadian society.

George was chosen by his village elders to go to Canada to make a better life for himself and to help his family and community back home, who were facing civil unrest and drought. It is easy to want to read into his facial expression on the photograph: scared, a little defiant, determined? On arrival, he immediately had to earn a living, and never had any formal education. He started by working as a labourer and a farmer in the segregated Chinese communities in Victoria and Vancouver. It took him 13 years, until 1936, to pay off the $500 Tax debt he had incurred on arrival to Canada. Adjusted for inflation, that $500 would be close to $7,500.00 today. Five years later, in 1941, he was lucky enough to be able to marry a woman of Chinese descent, Yuen (Lorna) Lim, a 17-year-old from Cumberland, BC. Lorna was born in Canada and had status as a British subject which she lost when she married George. At the time, when a woman married, she assumed the nationality of her husband who, in this case, was considered a Chinese national by the Canadian government.

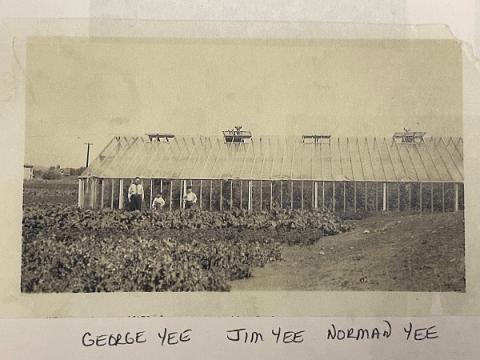

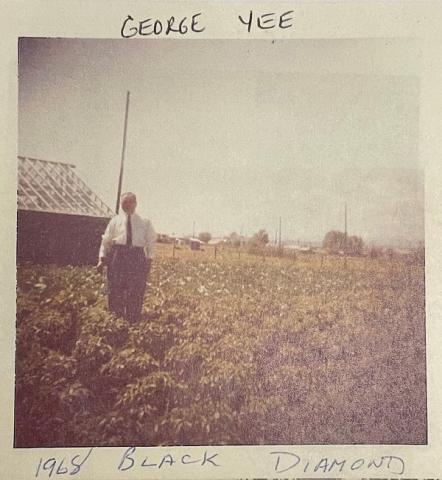

The couple settled in on a three-acre plot in Black Diamond, in the Turner Valley area, and raised eight children. They had a market garden in their field and greenhouse, some cattle in a small pasture, and even operated a small shingle mill. The Yee family was one of only three Chinese families in town, and the children remember experiencing some discrimination. Hard work was needed to survive, even as the area was benefiting from an oil boom. George would drive all day in his truck between local communities to sell their produce, which included potatoes, carrots, cabbage, and lettuce. After living and working in Canada for over 30 years, George finally became a Canadian citizen in 1958.

Working as hard as he did, George never made it back to his village, and died almost 30 years before the government’s official apology for the discrimination faced by Chinese people like himself. In 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an official apology to victims of the injustice of the Head Tax and the Chinese Immigration Act:

On behalf of all Canadians and the Government of Canada, we offer a full apology to Chinese Canadians for the head tax and express our deepest sorrow for the subsequent exclusion of Chinese immigrants… For over six decades, these race-based financial measures, aimed solely at the Chinese, were implemented with deliberation by the Canadian state. This was a grave injustice, and one we are morally obligated to acknowledge. To give substantial meaning to today’s apology, the Government of Canada will offer symbolic payments to living head tax payers and living spouses of deceased payers. (You can read the full speech here. )

As the living spouse of a payee, Lorna was issued a symbolic payment of $20,000 to redress the historic wrong. Of the estimated 82,000 Chinese who had paid the head tax from 1885 to 1923, only 785 were able to make a claim for ex gratia payments. While some descendants are satisfied with the government’s apology, others call for the government to acknowledge that redress is incomplete and to expand eligibility to the ex gratia payments to include the surviving children of Head Tax payers, on the principle of one certificate, one claim. A recent MacLean’s article details more on this struggle.

The Head Tax certificate in RAM’s collection is a rare survival of this shameful era of Canada’s past. Many early immigrants didn’t speak to their children about their past, and indeed, George’s children only realized that he paid the Head Tax after he had died. You can read more about George’s story, and his children’s recollections here.

It appears that only two other head tax certificates are held in public archives in Alberta; one for George’s close contemporary Edward Mah is at the Glenbow Archives, Calgary, and the other is a 1919 certificate for Leng Wing Mah in the Bruce Peel Special Collections library at the University of Alberta. They and other Chinese immigrants whose names are not preserved in public history records bore the brunt of racial discrimination in order to build a better life for their descendants. We should remember their sacrifices and work to ensure that they are never again necessary.

RAM is proud to be located at the south end of Edmonton’s historic Chinatown. Join us in solidarity with our neighbours, and please see these resources to help #StopAsianHateAlberta and support local Asian-owned businesses.

This post draws on research done by K. Linda Tzang, former Curator, Cultural Communities, and the recollections of the Yee siblings, held in RAM files.

NOTE: This text was corrected on December 12, 2022, to delete the claim that Lorna Lim lost her citizenship by marrying George Yee. In fact, under the laws of the time, she did not have citizenship. Thank you to June Chow, Archivist, The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act.