The Chicken Inn across the road

By Mathew Levitt, Digital Media

Feb 23, 2018

A half-century ago, if you stood on our downtown museum’s doorstep, you would have looked down what was then 98th street to Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn [1], an important focal point for the city’s Black community. Like the New York neighbourhood it references, the Harlem Chicken Inn was a meeting place where culture and community flourished.

(Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn, 10283-98 Street. Courtesy Myrna Wisdom)

To get a better sense of the vibrant community the Harlem Chicken Inn fostered, I met with Hatti’s granddaughter, Rosalind Harper earlier this year. As Rosalind’s parents were musicians and away on the road a lot, Rosalind lived with her grandmother, Hatti: “she practically raised me.”

All the dishes at the Inn were Hatti’s recipes. The signature dish, and Rosalind’s favourite, being just what you would expect: “since it was a Chicken Inn, obviously chicken…It was very popular.”

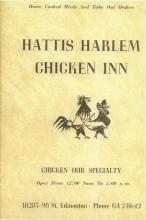

(A menu from the 98th street location. Courtesy Myrna Wisdom)

According to Hatti’s niece-in-law and long-time employee, Betty Melton, The Chicken Inn was known as “the best chicken in town. It was the first of its kind. When Americans would come to town, they would be told at the airport to check out Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn. That’s how well known it was.”

(Ad c. 1944. Courtesy Myrna Wisdom)

Hatti’s History

(Hatti Melton. Courtesy Debbie Beaver)

Hatti Robinson was born in 1903 and raised in the Amber Valley area, one of a few rural communities settled by Black families in the early 20th century.

Myrna Wisdom, an amateur [2], historian who has played an important role in documenting and telling Alberta’s Black history, explained that Hatti lost her parents when she was in her teens. Her mother and father were both ill and had asked a boarder of theirs, Peter Melton, to make sure their children were taken care of. Not long after they died, Hatti married Peter and the family moved to Calgary.

It was there that Hatti learned the tricks of the restaurant trade from Peter’s brother, Bob Melton, who ran the popular establishment, The Chicken Inn. After years of working in the Chicken Inn, Hatti eventually decided she could do it herself.

She opened Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn in Edmonton in 1944. According to one source, the Chicken Inn was first located at 101st street and 104th avenue, just west of Edmonton’s CN Tower. By 1949, the restaurant had moved to where the downtown Edmonton Law Courts now stand.

According to Rosalind, “It was around the time the soldiers were coming into the CN Tower. [3] They’d always gyrate towards the restaurant [about a block and half away]. So, grandmother catered to them. And they kept coming back and coming back.” The Harlem Chicken Inn was a favourite amongst musicians and celebrities, too, such as Big Miller, Pearl Bailey, and Tommy Banks who once said, “she put Colonel Saunders to shame” [4].

Hatti’s was much more than just a restaurant, however. Myrna shared that, “it was sort of a meeting place… If you were Black and you came to this city, you knew about Hatti’s… That’s where you could go and get a good meal and you would meet other black people there… That was one of the, well, I guess the meeting place for a lot of the people.”

Having come to the city as a young Black woman, Hatti took care of others in a similar situation. “That’s the only place they could get work unless you wanted to be a domestic. Especially the young women. So they would find work at the Harlem.” Even Rosalind worked at Hatti’s toward the end of its run in the mid-1960s.

(The Peoples Weekly, 1949, Peel’s Prairie Provinces Ad00803_3)

Working at the Inn, Rosalind learned both the culinary arts and the art of being social. “I learned how to interact with people like I’m interacting with you…that’s from working in the restaurant with my grandmother….you have to learn how to interact with the customers and be personable and they’ll keep coming back and coming back.”

Hatti’s personality set a comfortable community atmosphere. “That was her forte,” says Rosalind. “She looked after everybody: the men, the soldiers, and that was their stomping grounds, you know. There was no trouble caused.”

Hatti’s legacy

In 1967 the Harlem Chicken Inn moved from its longstanding place in the Senate Hotel on 98 street when the development of the Law Courts began. In 1969, Ms. Hatti Melton, proprietor, aged 66, passed away. A short while later, the restaurant closed its doors for good. Hatti’s daughter, Myrtle, had given running the place a shot, but according to Rosalind, “that wasn’t her forte”.

Leafing through old phone books, one can see that by 1967 there were other chicken joints like Dixie Lee Fried Chicken, Jack’s Chicken Inn, and, a few years later, a Chic’N Inn. In Rosalind’s opinion, though, none of these places compared: “the chicken never did taste the same”.

(Hatti and her daughter, Myrtle. Courtesy Debbie Beaver)

Although the restaurant is gone, Hatti’s true legacy remains. “[Hatti] was always helping somebody. And then, of course, it went down the line…I was raised and that’s what I did. I helped people.” Not only that, Rosalind “learned to accept people for what they are. And they appreciated that…I learned all that from my grandmother again. You accept people for who they are.”

The memory of Hatti and her Harlem Chicken Inn is a collective one. She is remembered for being a humanitarian, for employing young Black people, many from rural communities like hers, who needed someone on their side, and for helping to make downtown Edmonton a more welcoming community. She even sponsored a local ladies softball team: The Harlem Chicks.

(The Harlem Chicks. Courtesy Debbie Beaver)

Myrna, explained why the story of the Harlem Chicken Inn is important to share: “I just feel that she should be remembered, you know, given the fact that she was one of, if not the first Black business to operate in the city…She managed to make a living for herself but she also recognized that young Blacks – men and women – needed a start and working for her, well she provided that for them.”

Gathering loose threads

The neighbourhood the new RAM sits in has changed a lot since Hatti’s time. From her restaurant, Hatti would have seen many new beginnings like the building of the new City Hall and the CN Tower. And while she did not live to see the ending of her own restaurant, I wonder: maybe we haven’t seen that ending either.

The story of Hatti’s Harlem Chicken Inn is all around us: in local community history books, online articles, in personal testimonies, in photos and newspaper articles, in the memories of those who knew Hatti and went to her restaurant. Threads stretching out in space and time, and precious ones at that. With the help of our community partners, we are trying to gather these threads together, to weave visible what might otherwise be subtle and hard to see. When I tug on these threads, I still feel pulled to that Chicken Inn across the street.

[1] Hatti is often spelt Hattie. There is no ‘e’ according to the menu, ad, and most telling of all, the storefront, but Hatti does have an ‘e’ in the Henderson directories and her obituary…I will refer to her throughout as Hatti.

[2] That term, “amateur,” isn’t disparaging. I use it here in the true sense of the word; “to love” something with passionate pursuit, without compensation.

[3] The CN Tower was built in 1966, a few years before Hatti’s closed. Before the tower was the CNR Edmonton station, which was demolished in 1953.

[4] Tommy Banks, Interview, 1 May 2007, Black Settlers of Alberta and Saskatchewan Historical Society.