The Bowen Residence: A Community Hub in Amber Valley

By Matt Ostapchuk, Curator, Military and Government History; With support from Myrna Wisdom

February 24, 2025

On December 29, 2020, a fire destroyed a historic site that was once at the heart of the community of Amber Valley. The Bowen Residence, also known as Obadiah Place, was associated with the Black settlers who founded Amber Valley from 1910-1912, having left the United States amid increasing racism, segregation, and violence. Though the settlers continued to face racism in Canada, the community prospered and built a school, an interdenominational church, and established a post office. The Bowen Residence served as a hub of the community and was home to two prominent community leaders—Willis Reese Bowen and his son Obadiah Bowen. Shortly after the fire, the Royal Alberta Museum learned that an important element of the historic site survived—Amber Valley’s public phone booth.

Originally from Alabama, Willis Reese Bowen and his wife Jeanie Bowen (née Thigpen/Gregory) first moved to Texas before relocating to the Oklahoma Territory. In Memories of My Father, The Late Willis Bowen of Amber Valley, Alberta, their daughter Willa Dallard recalled that “Oklahoma, when we first arrived there, was still just a Territory, and the relations between Blacks and Whites were very cordial. My people prospered in Oklahoma. We owned our farms, worked hard, and unlike those who stayed in Alabama and the other States, all of the children got a fairly good education.” With statehood in 1907, came segregationist Jim Crow laws, racial hostility, and violence. “So my father, always ambitious and proud, wanted to go where every man was accepted on his merit or demerit, regardless of race, colour or creed. So in the summer of 1909, we moved to Canada.”

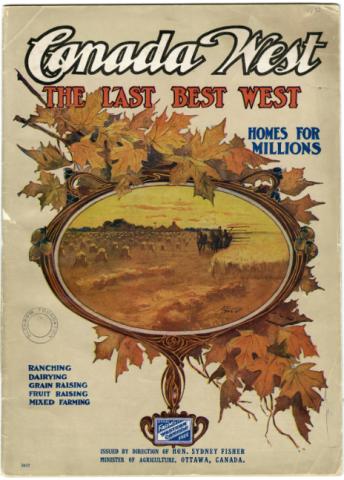

Between approximately 1908 and 1911, more than 1,000 Black settlers immigrated to Alberta and Saskatchewan from Oklahoma and surrounding states. Attracted by the Canadian government’s “Last Best West” campaign to draw homesteaders to the Canadian Prairies, the settlers established the communities of Pine Creek (renamed Amber Valley), Campsie (Barrhead), Junkins (Wildwood), and Keystone (Breton) in Alberta, and Maidstone in Saskatchewan.

The arrival of large groups of Black settlers was met by racism in Canada. While the Canadian government was attempting to attract immigrants to the prairies, the government had preferences along racial lines. To deter and prevent Black immigrants from entering Canada, the government employed various methods and policies, including a disinformation campaign targeted at prospective Black American settlers (see The Last Best West).

The Bowens were not among the first group of families to settle in Amber Valley in 1910. Instead, they opted to move to Vancouver. Willis Bowen chartered a special railway car for five families and a couple of bachelors to travel to Vancouver. After initially being turned away by customs officials (apparently because one of the children had a broken leg in a cast), the Bowens eventually made it to Vancouver. After tragedy struck, with the family losing their baby girl Altha to illness, the Bowens decided to relocate to Amber Valley. In 1912, Willis, Jeanie, and their 10 children travelled to Edmonton by train, then overland by wagon to Athabasca, and finally on to Amber Valley.

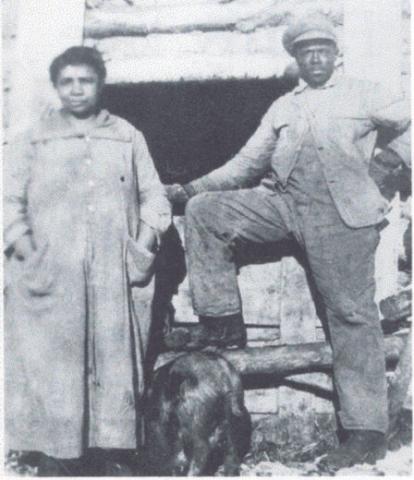

Once in Amber Valley, Willis filed for a homestead and built a hewn-log house with the help of neighbours. Dallard described their initial home:

“We had two rooms downstairs and one big room upstairs, which was curtained off so the boys slept in one part and the girls in the other. The front room was Mom and Dad’s bedroom. But we got one of those davenports, so it was curtained off at night when used as a bed. And by day the curtain was drawn back leaving a not-too-bad parlour room.”

In Amber Valley, the Bowen family grew to 12 surviving children. In addition to farming, the family hunted, fished, and worked a variety of jobs to sustain themselves. Willis regularly hauled freight.

When Amber Valley established its own post office in 1931, the community changed its name from Pine Creek to Amber Valley. Prior to 1931, Pine Creek shared postal service with neighbouring Donatville. Samuel Carothers, who was located near the border of the two communities, operated the Donatville post office and store, and a blacksmith shop. Myrna Wisdom—Samuel Carothers’ maternal granddaughter and Willis Bowen’s paternal granddaughter—notes that, “Sam Carothers was the first Black man in Alberta to be granted a permit to operate a post office.”

With the new community’s name and post office, Willis Bowen was appointed as Amber Valley’s first postmaster on September 5, 1931. The Bowen family operated the post office from their homestead until 1942—first out of the original log house, then out of the second house after it was constructed in 1938. (Note: This article henceforth refers to the second Bowen Residence as Obadiah Place to avoid confusion.)

Willis and Jeanie’s son, Obadiah, married Eva Mae Mapp in 1936. To accommodate the growing family, Obadiah replaced the log house in 1938, constructing a larger house that is commonly referred to as Obadiah Place. The Canadian Registry of Historic Places describes the house as “a one and one-half storey square prairie vernacular wood frame building.” The original floorplan featured a “central hall, staircase, kitchen, dining space, parlour and bedroom (main); bedrooms and bathroom off a square hall (second floor).” The home also included a 1959 addition to the rear elevation.

Like his father, Obadiah farmed on the original homestead with his wife and eight children (this includes his baby daughter, Yvonne, who died in 1941), and worked a variety of jobs to support the family. A community leader, Obadiah donated land to build a new church and served as a pastor, delivering sermons at the interdenominational church.

Nettie Gertrude Murphy took over the post office in 1942. Wisdom recalls, “The Murphys ran the post office, public phone, a store and gas station.” When her residence was destroyed by fire, Amber Valley needed a new location for the public phone (Murphy’s daughter Jettieree Brown had taken over the post office).

The size and location of Obadiah Place at the centre of the community had already made the home a gathering place; this made it an ideal location for the phone. Wisdom recounts:

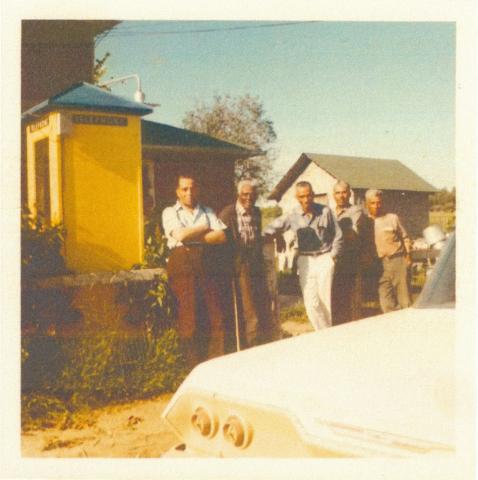

“In [approximately] 1962/63, a public phone was installed in the Willis Bowen home which he shared with his son Obadiah and his family. This short-term intervention proved very intrusive, giving rise to the installation of a public phone and phone booth in the Bowen yard. Party lines were initiated for a short time, followed by individual private phone lines. The public phone was removed but the phone booth remained in the Bowen yard.”

By the 1960s, Amber Valley had experienced decline. The school closed in the 1950s and the post office in 1968. Writing to the Editor of the Edmonton Journal in 1963, J. Edwards of Amber Valley explained that the community had “lived up to its good name with a good school, church, leading sportsmanship, particularly in baseball; and both inside and outside activities such as concerts, banquets and picnics.” The Edwards family was among the first settlers who established the community in 1910. Addressing the decline, Edwards noted that: “Many young people grew up in Amber Valley, making brilliant scholars and going on to educational fields, fitting themselves and acquiring positions that took them away from the farm to the cities.” For example, Oliver Bowen—one of Obadiah and Eva’s children—became an engineer and managed the design and construction of Calgary’s original light rail system (the CTrain).

While Jeanie Bowen passed away in 1932, Willis remained in Amber Valley on the homestead until 1970, when he moved to a nursing home in Athabasca at the age of 95. Willis lived to be a centenarian, passing at the age of 100. Obadiah also stayed in Amber Valley, living in the house he built until 1996, when he also moved to Athabasca. Eva had passed away more than two decades earlier in 1972. Obadiah died in 2004, at the age of 96.

Obadiah lived to see his home recognized as a Provincial Historic Resource in 1999 by the Province of Alberta. The home, ancillary outbuildings, and phone booth were identified as a character-defining elements of the site. Once the site received historic designation, work began to restore the house to its former condition, including restoration of the horizontal cedar siding. Sadly, the house was destroyed by fire on December 29, 2020.

Approximately nine months later, we, the Royal Alberta Museum, were contacted about a potential donation. It turned out that, prior to the fire, the phone booth had been removed from the site and was undergoing restoration. As a result, this is one of the last surviving elements of the historic site.

We were asked if we would accept the phone booth into our collection to ensure that it is preserved for future generations of Albertans. As the phone booth represents the Bowen family’s and the historic site’s significance and connection to the community, we gratefully accepted this important piece of Alberta’s history.

We’d like to extend a special thank-you to Myrna Wisdom for gathering and sharing information for this article.